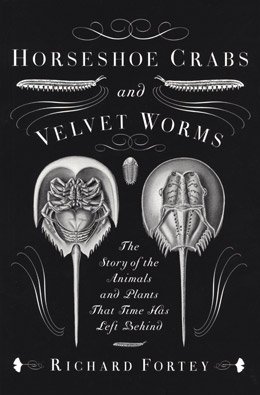

Velvet Worms and Horseshoe Crabs, Richard Fortey

Velvet Worms and Horseshoe Crabs, Richard Fortey

The great question of paleontology or biology or ecology—all the life sciences really—is how did we get to where we are now? Where (and when) did all these species come from? How did the current mix come to be? And, relatedly, what lets some species (or genera, family, order, etc.) survive when others went extinct?

Velvet Worms and Horseshoe Crabs explores these questions by looking at the species – bacteria, plans, fungi, and animals – who have survived. Things like horseshoe crabs, the only survivors of a once-sprawling (order? Class? I forget) that included trilobites and others back in the day. Other living fossils include creatures such as the extremophiles in Yellow Stone, the Australian monotremes, ferns and other of the earliest plants, and stromatolites, possibly the longest existing form of life on earth. These microbial colonies were likely here 3.5 billion years ago.

Each of the essays in this book was interesting in its own way. I like nature writing. I like learning about weird creatures, like clams that have managed to live in high methane environments. I am morbidly interested in past mass extinctions; in a weird way they give me hope about what we might see on the other side of this one. But I didn’t think there was a through line in the book. Fortey discusses these living fossils and why he is seeking them out frequently; he talks about learning the ways species stay the same and how they change, emphasizing that there is no true living fossil. Even something like the horseshoe crab or the crocodile has changed itself over time.

All of this, as I mentioned, is interesting. But it does not really answer the questions it was set out to answer. Are there any similarities? Is there any lesson? Maybe there isn’t, and that’s okay, too. Perhaps this are all just natural curiosities. I just wanted a bit more of a thesis, a bit more understanding of why this was a book and not just his own fun group of field trips around the globe. I also felt that in his effort to showcase many different groups, some were shoehorned in. In the discussion of salamanders, for instance, he is honest that it’s difficult to figure out which of the amphibians are closest to former ancestors. If this is the case, then perhaps leave them to the side. Look more at insects or arachnids or dive more deeply on the plant and fungus kingdoms. Instead, it seemed that a couple of the chapters were checking off a list rather than adding to the already-thin thesis. And, most unforgivably, during some of these I even started to get bored. And so I have to say that there are other books who cover weird animals, extinctions, or globe trotting with more wit and insight. It may be better to spend your reading time with them.

Filed under: Book Reviews, books, Environment, science | Tagged: biology, evolution, horseshoe crabs, living fossils, paleobotany, richard fortey, science, velvet worms | 1 Comment »